Hasmoneans on the Brink of the Abyss: Internal War, Vile Politics, and Spiritual Ruin

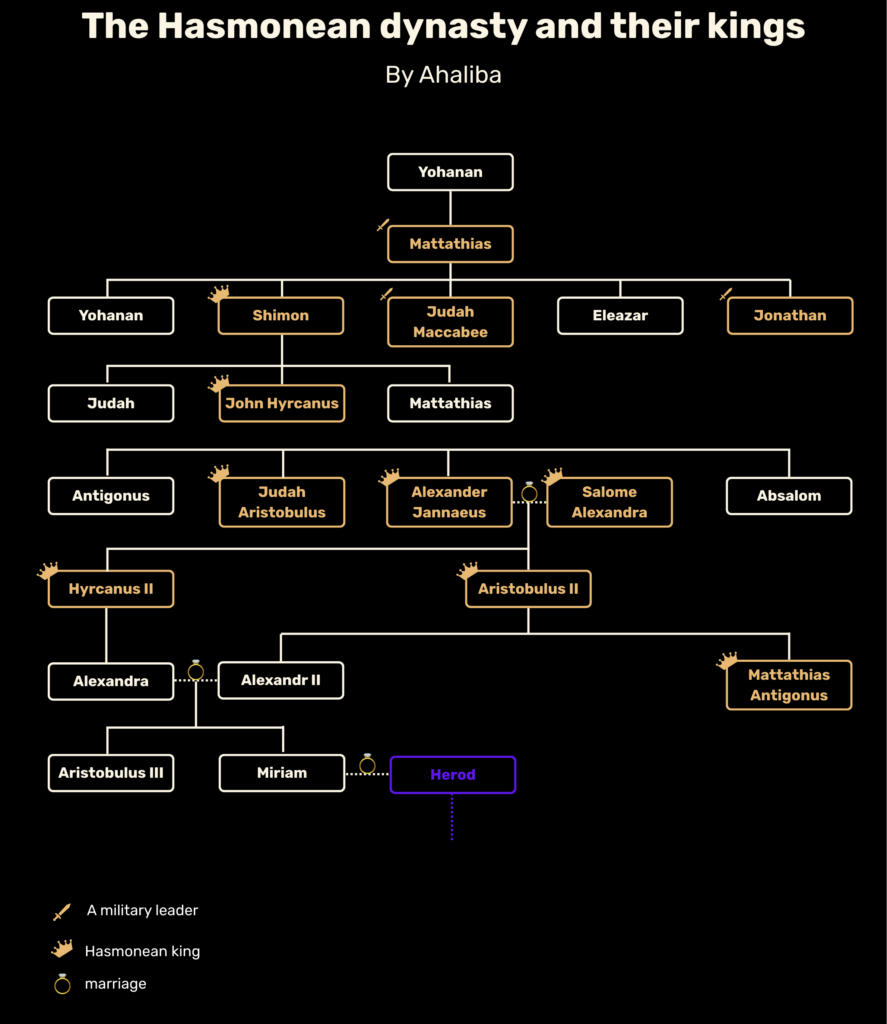

The tension between the Pharisees, beloved by the people, and the Sadducees, the aristocratic elite, only intensified. Hyrcanus was aligned with the Pharisees’ approach and the Temple service, while Aristobulus was close to the Sadducees and the military leaders. Aristobulus succeeded in his rebellion, rallying many army commanders to his side. Hyrcanus sent the army loyal to him to fight Aristobulus, but many of Hyrcanus’s soldiers deserted, some even joining Aristobulus. Hyrcanus and his wife and children fled to a fortress in Jerusalem where Aristobulus’s wife and children were imprisoned. Seeing that he had no chance of winning this war, Hyrcanus agreed with his brother: he would relinquish the kingship and the High Priesthood to Aristobulus, and in return, Aristobulus would allow him to live out his days in peace with great wealth. They swore to this with a handshake and embraced each other in front of the people. To strengthen the bond, they also arranged a marriage between their children—the daughter of Hyrcanus wedded the son of Aristobulus—and everything ended peacefully, but only for a very short time.

Antipater came from a prominent Edomite family from southern Negev, which had converted to Judaism during the time of John Hyrcanus as part of a mass conversion campaign Hyrcanus conducted among the people he conquered. Antipater resided in Jerusalem and devotedly supported Hyrcanus, strongly opposing Aristobulus. After Hyrcanus relinquished power, all those close to him began to fear for their lives and status. Antipater convinced Hyrcanus that Aristobulus would eventually kill him and persistently suggested that Hyrcanus had needlessly given up the kingship and High Priesthood, as the people supported him and favored his rule. He persuaded Hyrcanus that he would help him reclaim the monarchy. At first, Hyrcanus was unconvinced, but after some time, he relented. One night, Antipater smuggled Hyrcanus out of Jerusalem and took him across eastern Transjordan to Petra, the capital of the Nabataean kingdom. There, Antipater connected Hyrcanus with the Nabataean king, Aretas III. Antipater managed to convince Aretas to assist Hyrcanus. In return, Hyrcanus promised that if he became king, he would return to Aretas various regions and cities that previous Hasmonean kings had captured.

Aretas, Antipater, Hyrcanus and their men set out to wage war on Jerusalem, laying siege to the city. Then, a reversal occurred—many people who had been loyal to Aristobulus abandoned him and joined Hyrcanus and his forces. The siege was very severe, and Aristobulus was left alone in the end.

The Gemara in Massehet Sotah recounts: “When the Hasmonean kings besieged one another, Hyrcanus was outside and Aristobulus was inside. Every day, they would lower dinars in a basket and raise the daily offerings (there was an agreement between the brothers—though they were at war, the Temple service had to continue, and each day, one side would give money to the other to bring the sacrifices to the Temple). There was an elder there who was versed in Greek wisdom. He mocked them (Hyrcanus’s men outside the walls of Jerusalem), saying, ‘As long as they are engaged in the service (as long as Aristobulus’s men offer sacrifices in the Temple), they will not be delivered into your hands’ (you will not defeat them because God is with them when they perform the Temple service). The next day, they (Aristobulus’s men) lowered dinars in a basket, and those (Hyrcanus’s men) raised a pig. When it reached halfway up the wall, the pig dug its hooves into the wall, and Eretz Israel trembled four hundred parasangs by four hundred parasangs. At that moment, they (the sages of Israel) said, ‘Cursed be the man who raises pigs, and cursed be the man who teaches his son Greek wisdom.'” This story vividly illustrates the profound spiritual decline of the Hasmonean kingdom. The pig was a symbol of the Greeks forcing Israel to abandon their religion, one of Antiochus’s decrees being to compel Jews to eat pork. In that era, Jews were willing to die rather than eat pork, and this was precisely what the sons of Mattathias fought for. The punishment for this act was immediate and economical: that year, when the pig incident occurred in Jerusalem, there was no harvest, leading to a severe famine and drought.

Read about Alexander Jannaeus in an Empire of Blood and Power here

Hasmoneans at the Stake: The Rift That Brought Rome to the Gates of the Temple

The brutal war between the brothers ended with the emergence of a new military power in the region—Rome. As the Seleucid kingdom weakened, the Romans gradually approached the regions of Asia and the Middle East. One of Rome’s most prominent commanders was Pompey. Pompey set out on campaigns in the East, even defeating the king of Armenia, who was considered a powerful ruler, and began waging war against the already weakened Seleucid kingdom, which Antiochus XIII then led. He conquered all these kingdoms, turning them into vassal states under his control and appointing a Roman governor to manage each one. While fighting in Armenia, Pompey sent one of his army commanders, Scaurus, to battle the Seleucid kingdom. However, other Roman commanders conquered the Seleucid kingdom in the meantime, so Scaurus set his sights on the kingdom of Judah, which he decided to conquer.

When Scaurus arrived in Judah, both brothers sent delegations to him, seeing a great power approaching. Aristobulus promised him wealth and brought him a lavish gift. Though Hyrcanus also made promises, he was less convincing than his brother. Consequently, Scaurus came to Jerusalem and forced the Nabataeans and Hyrcanus’s forces to lift the siege on Jerusalem, threatening that if they did not, they would be declared enemies of the Romans. Thus, Aristobulus was saved from the siege. When Scaurus headed back toward Damascus, Aristobulus pursued Hyrcanus and Aretas, killing many of their men.

After Pompey completed his campaigns in the Black Sea region, he arrived in Damascus, the capital of the Seleucid kingdom. As everyone recognized him as the dominant power in the region, delegations from across the Middle East, including Judah, came to present their grievances to him. In the spring, three delegations from Eretz Israel arrived before Pompey: one from Hyrcanus, another from Aristobulus, and a third from the people as an independent entity. The people requested that Pompey free them from the rule of the Hasmonean brothers, asking to be governed by the priests instead. They argued before Pompey that, although the Hasmoneans were originally priests, they had long abandoned the ways of the Torah and Judaism. Hyrcanus claimed to Pompey that he was the firstborn and that Aristobulus had taken the monarchy from him by force, describing Aristobulus as a negative influence, a pirate (something the Romans fiercely opposed), and a troublemaker for the entire region. Aristobulus, in contrast, arrived like a king, with great pomp and a retinue before him. He explained that he was the king and ruler of the land, asserting that he had taken power from Hyrcanus because Hyrcanus was a weak ruler.

Pompey listened to the claims of all sides and seemed inclined toward Hyrcanus. He asked them to wait until he finished dealing with an issue in the Nabataean kingdom, after which he would address the dispute in Judah. However, Aristobulus sensed Pompey was not in his favor, so he began blocking roads and inciting the inhabitants against Pompey and the Romans. This greatly angered Pompey, prompting him to abandon his other engagements, take his army, and set out to conquer Judah. Aristobulus tried to stop him with peaceful overtures and surrender, but he and his men did not adhere to the terms of surrender he had agreed upon with Pompey. As a result, Pompey arrested Aristobulus and began a siege on Jerusalem.

Within Jerusalem, there was a debate about how to proceed. One group argued they should surrender to Pompey to prevent harm to Jerusalem, while another insisted they must fight and not give in, lest he enter the Temple. With Hyrcanus’s encouragement, Pompey succeeded in entering the city and conquering large parts of Jerusalem. Eventually, the Romans breached the Temple, desecrated it, and killed everyone inside. Pompey did not touch the Temple treasures; the next day, he ordered the remaining priests to purify the Temple and resume offering sacrifices. Pompey executed all of Aristobulus’s associates and detached various regions and cities, including eastern Transjordan, from the Hasmonean kingdom, thus turning the Hasmonean kingdom into a vassal state of the Roman Empire. In 63 BCE, the independent Hasmonean kingdom came to an end. From that year onward, Judah was no longer an independent kingdom, and its rulers were subject to and controlled by the Romans.

Hyrcanus and Aristobulus brought this disaster upon Jerusalem through their conflict with each other. By doing so, they forfeited their freedom, became subservient to the Romans, and were forced to relinquish the land they had acquired with their weapons. The authority previously held by the High Priests became an honorary position for individuals within the community. Thus, it was the brothers’ struggle and internal discord—not religious decline alone—that led to the arrival of the Romans and, ultimately, to the destruction of the Temple.

Hyrcanus was appointed High Priest and local leader (not king), while Aristobulus was taken captive to Rome and displayed in Pompey’s triumphal procession. One of Aristobulus’s sons, Alexander, escaped from Rome, returned to Israel, gathered a large army, and launched a military revolt against Hyrcanus and Roman rule. The Roman military commander in Israel, Gabinius, went to war against him and managed to suppress the revolt. Alexander surrendered, sought forgiveness, and was returned to captivity in Rome. Aristobulus escaped from Rome a few years later, returned to Israel, and started another revolt. Still, Gabinius suppressed this revolt as well and sent Aristobulus back to captivity in Rome.

The Last King of the Hasmonean Kingdom

Aristobulus remained in captivity in Rome until 47 BCE, a significant year in Roman history when a coup took place against Pompey and Julius Caesar rose to power in his place. Julius Caesar released many prisoners captured by his predecessor, including Aristobulus, who was planning to send him to lead an army in Syria. However, Pompey’s loyalists, still present in the region, poisoned Aristobulus, and he was murdered that same year. His body was preserved in honey and later sent to the Hasmonean kings’ tomb in Israel. A similar fate befell Alexander, Aristobulus’s son, who Pompey’s supporters also killed. The rest of Aristobulus’s family—his wife, son, and daughters—were sent to Ashkelon under the protection of the son of one of the northern rulers. Their protector fell in love with Aristobulus’s daughter, Alexandra, and married her. Among those sent to Ashkelon with Aristobulus’s family was Mattathias Antigonus II, Aristobulus’s only surviving son.

Hyrcanus held the position of High Priest and leader of the Jews in Judah. Still, he was a very weak ruler, and the one effectively managing affairs was Antipater the Edomite. Meanwhile, power struggles unfolded in Rome, and Julius Caesar took control, leading to a battle that resulted in Pompey’s elimination. Antipater aided Julius Caesar, who, in gratitude, appointed him the de facto overseer of Judah while keeping Hyrcanus as High Priest. Antipater had several sons, two of the most notable being Phasael and Herod. Due to Hyrcanus’s weakness, Antipater took full control, appointing Phasael to oversee Jerusalem and its surroundings and Herod to manage Galilee at the age of 15. Despite his young age, Herod proved highly effective, eliminating rebel forces in Galilee and earning great acclaim among the Roman governors in Syria.

Hyrcanus completely lost his power to Antipater and his sons. He summoned Herod to trial for killing a Jew from Galilee named Hezekiah. Still, when this became known to the Roman governor, he sent Hyrcanus a stern letter demanding Herod’s release and forbidding his execution. Josephus Flavius, in his ancient book The Antiquities of the Jews with the Romans, describes the trial in a muted tone, noting that Hyrcanus, due to the letter from the Syrian governor, released Herod. Herod fled to Damascus and attempted to gather an army to attack Hyrcanus, but his father and brother Phasael stopped him. Herod harbored a grudge against Hyrcanus and his house.

In 44 BCE, Julius Caesar was assassinated, sparking a titanic struggle within the Roman Empire over his succession between Cassius, one of his assassins, and Marcus Antonius, a supporter of Julius. This conflict sent shockwaves throughout the empire, with attempted revolts suppressed by Antipater and his sons. Malichus, one of Hyrcanus’s close associates, was a scheming man saved from death multiple times by Antipater. Despite this, he orchestrated a plot and poisoned Antipater to death. Herod avenged his father’s death by ensuring Malichus was killed. Herod was furious with Hyrcanus, believing he had sent Malichus, so to appease Herod, Hyrcanus betrothed his granddaughter Mariamne the Hasmonean—who was a Hasmonean on both sides—to Herod. Mariamne was the daughter of Alexandra, daughter of Hyrcanus, and Alexander, son of Aristobulus. When the brothers, Hyrcanus and Aristobulus, fought over the monarchy, they married their children to each other to ally. Mariamne was the granddaughter of both brothers, born from this peaceful marriage.

Meanwhile, in Rome, the faction supporting the assassinated Julius Caesar succeeded in seizing power. The Jews then approached the new Roman ruler, Marcus Antonius, requesting that he free them from the oppression of Herod and his brother Phasael. Still, Antonius rejected their plea and maintained the status quo in Judah. This did not last long. The Parthian Empire, recognizing the Roman Empire’s weakness amid its internal struggles, decided to launch campaigns to strengthen its position in the region, conquering Syria and beyond. Mattathias Antigonus understood this situation.

Mattathias Antigonus, Aristobulus’s son, had been with his mother and sisters in Ashkelon before moving north to Lebanon. Initially, he tried to incite a revolt in Galilee, but Herod suppressed it. At this stage, as he observed the Parthian Empire’s movements, he joined them, rallying many Jews who were fed up with the rule of Antipater and his sons. Together with the Parthian army, they successfully conquered Eretz Israel. They reached the gates of Jerusalem and came to the festival of Shavuot, when many Jews gathered in Jerusalem, some armed and some unarmed. The Parthian forces requested permission from Phasael to enter Jerusalem to calm the Jewish forces causing disturbances within the city.

Herod opposed the idea of the Parthians entering Jerusalem, but Phasael and Hyrcanus were convinced it was the right thing to do and allowed a Parthian contingent to enter. The Parthians entered Jerusalem and began conquering the city, persuading Phasael and Hyrcanus to surrender. Thus, Phasael and Hyrcanus were taken captive in Babylon. Phasael smashed his head against a rock and committed suicide. At the same time, Hyrcanus was taken into captivity, where his ears were cut off (a practice common in the Parthian Empire for enemies). Herod fled with his army, taking his family—his wife Mariamne the Hasmonean, her sisters, her mother, and her grandmother (the entire Hasmonean royal family of Hyrcanus)—and Mattathias Antigonus was installed as king over Judah by the Parthians.

Mattathias Antigonus reigned for only three years. The Romans did not tolerate the Parthian conquest and launched a campaign to reclaim the territories taken from them. Herod attempted to reconquer Jerusalem, facing several battles in which he was repelled northward from Jerusalem, but he gradually managed to take control of Galilee. Mattathias Antigonus fought against forces loyal to Herod in the region, and in one battle near Jericho, he succeeded in killing another of Herod’s brothers, Joseph. However, the tide then turned. The Romans defeated the Parthian army and expelled them from the region. Marcus Antonius, the Roman Caesar who greatly favored Herod, sent the Roman army to assist him, and against the Roman army, Mattathias Antigonus stood no chance. Herod, together with the Roman army, reached Jerusalem and besieged it. Mattathias surrendered and was taken to Damascus, where Marcus Antonius executed him at Herod’s recommendation, who argued that as long as a scion of the Hasmonean house remained, there would never be peace in the kingdom of Judah.

The Hasmonean kingdom was left without any heirs; all the family members had died or been murdered. Only the daughters remained, who could not serve as priests, and their sons followed their father’s lineage, thus ending the days of the Hasmonean house. The holy revolt that began with Mattathias, who raised the banner of rebellion with the cry “Whoever is for the Lord, come to me”—the courageous High Priest who feared God and upheld the Torah’s commandments alongside his sons—concluded with Mattathias Antigonus. The revolt, which started as a religious uprising to sanctify God’s name and led to political independence grounded in religious strength, such as inscribing God’s name on coins and enjoying the full support of the people and Torah sages, within a relatively short time began to be influenced by surrounding cultures. Its religious resilience and the purpose for which it was established eroded. From the death of Simon, son of Mattathias, onward, the Hasmonean house grew distant from the people and the path of the Torah. There followed a prolonged decline of the Hasmonean kings, first religiously, then socially, culminating in the wars between the brothers. What began with great promise ended in bitter disappointment, as the rule over the Jewish people became Herod’s dominion under the practical subjugation of the Roman Empire, ultimately leading to the destruction of the Second Temple and the dispersion of the Jewish people into exile.

Credit: Written and edited from the series of lessons by Rabbi Zvi Haber, “Azi Bami Hashmanim.”